My new favorite concept is the “secretly mysterious.” My poet friend, Caitlin, is a prime example of this. On the surface, she is a warm, multitasking mom with a generous smile, quick to throw her head back with an appreciative chuckle. The surface speaks true. She is all of those things. She is all of them so wholeheartedly that you might never wonder whether there’s anything more to her. But there is.

Beneath the welcoming exterior, you might first find a mind as sharp as cleaver, severing the bones from the flesh of a thought in one swift stroke. Then, you find out she’s a scientist full of figures and data processing. Okay, that fits with that analytic mind. But then you discover she has been writing astonishingly tender poems for years and quietly abandoning them to moulder like dead leaves in the compost pile. Then you slowly begin to compute that her expressed beliefs are a smorgasbord of the left’s affirmation of the outcast and the right’s appreciation of a stable home and many things that don’t toe any party line. As you discover her, layer by layer, it dawns on you that still, you’ve only just scraped the surface.

“Microcosmoidon” is a word I coined in high school as an alternative for “human.” My ideas was that each of us is a cosmos in miniature form, conceived in a timeless moment, spiralling out from the initial burst of our birth, but dappled with the abysses of black holes. My secretly mysterious friends are wonderful reminders to me that below simple surfaces lie souls of infinite complexity. Which brings me to food.

Burnt-out Cooks Need Cleavers

To slice my veggies with a cai dao would be one small reminder that the cook can be an artist. That the housewife can be a priestess. That home cooking is worthy of respect.

I’ve been disenchanted with food recently, burnt-out on cooking. Normally, the rhythm of chop-chop, bang a cast-iron on the stove, whisk eggs, splash down pillars of milk is my personal meditation. But I’ve come into a block! My ingredients sit before me on the counter, useless lumps that I can’t imagine integrating into something lovely. Eventually, with titanic effort, they become a bowl of cold zaru soba with boiled eggs, or a Thai chicken curry. But it seems like a miracle each time, and as I scarf it down, I don’t remember the cooking process at all.

It’s like food has lost its soul. I’m seeing the surface: it’s good for eating. But without seeing deeper, I can’t be in love. I’m trying to remember that food is as secretly mysterious as my friends. It just takes some effort to break through the surface.

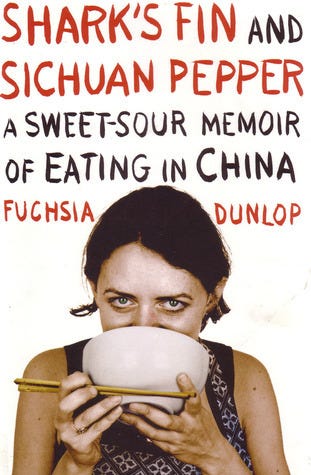

Today, my step towards that is to scour the internet and local thrift stores for cai dao cleavers and carbon steel knives. My latest and best read, Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China, extols the virtues of the multipurpose Chinese cleaver for paragraph upon paragraph. It’s the memoir of a British BBC writer and Chinese cooking enthusiast, focusing on her time spent in Chengdu in the 90’s as an aimless young professional. I liked the terror-factor of her cleaver descriptions, which made cooking sound glamorous and intense, and I liked her stories of sweet-talking corrupt Communist officials and hitching rides on motorcycles and oxcarts.

But really, beneath it all, the attraction of the knife is its deceptive simplicity. “Given the complexity of the art of cutting, you might expect the Chinese chef to have a whole armory of fancy knives,” Fuschia writes. “Nothing, however, could be farther from the truth. The instrument of almost all this artistry is the simple cleaver, a hammered blade of carbon steel with a wooden handle and a well-honed edge.” The beauty of fire-exploded kidney stars (火爆腰花—the Chinese characters look like exploding stars to me) is heightened by the knowledge that the chef carved the dish’s intricate shapes with one seemingly ungainly tool.

Then (imagine this), I began reading a 1969 book by an American episcopal priest, The Supper of The Lamb, and he recommended the very same cai dao knife, drawing attention to the way its wielding speaks of expertise. When a feminist sexist makes condescending comments about your decision to stay home and nurture your family, the author recommends that you invite him in while you are sharpening your cleaver: “Simply let him see you presiding over your kitchen with steel in one hand and butcher knife in the other. Execute six well-drawn strokes, and his words will turn to ashes in his mouth. He was ready only for a maladjusted prisoner of the pantry; you have showed him instead one of the priestly archetypes of the race.” The skill and danger of the honed knife demands respect towards its wielder.

To slice my veggies with a cai dao would be just one, small reminder that cooking hides a world beneath its plain exterior. That there is an entire “culinary cosmology” to discover in the market and the kitchen. That the cook can be an artist. That the housewife can be a priestess. That home cooking is worthy of respect.

Burnt-out Cooks Need Attitudinizors

Love is what makes a meal delicious.

Really, these two books are helping to restore to me a full view of eating by allowing me to see it through lover’s eyes.

One of my favorite authors is Stanley Weinbaum. He died young, leaving only a handful of short stories written for sci-fi pulp magazines. In one of these, “The Point of View,” the protagonist, Dixon Wells, is working on the “attitudinizor,” a pair of eyeglasses that allow one to assume the point of view of another person. As he tests them, he falls unexpectedly in love. Peering through the lenses, he finds himself faced with a goddess-like woman with full lips and glowing skin. But when he removes the glasses, she disappears. He soon realizes that he only sees her when assuming the point of view of one of his lab mates—and that the goddess is actually the exceptionally drab secretary he’s ignored for years. His lab mate is in love with her, and because of this, when he adapts his point of view, the drab secretary suddenly embodies the epitome of desirability.

Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper is acting as an attitudinizor for me with its loving perspective towards the kitchen. Listen to how Fuschia describes Cantonese food—”a steamed fish, treated lightly with ginger, green onion and soy; a stir-fry of slivered ingredients in which everything is perfectly crunchy or tender.” Could anything be more ardorous? She wraps these food descriptions in fine silk cloth woven from threads of friendship and love—”It was hard to imagine Xie Laoban being anywhere else but in that bamboo chair in the backstreets around the university, taking orders for noodles and barking at his staff.”

One can reduce food to simple sustenance—starch, protein, fat—and people to simple roles—mom, accountant, cook. But an attitude of curiosity can lead to love. And love is what makes a meal delicious. Food and people may be the basic ingredients of a meal, but you need to see the food in all its glory, and the people too, before the meal reaches its apotheosis.

With this in mind, I must go. It’s time for me to cook dinner.

These are inklings that might turn into an essay by the end of the summer. Hit me with reading recs and extol to me the virtues of food, glorious food and your ways of re-recognizing its beauty.

“below simple surfaces lie souls of infinite complexity” — has been dawning on me ever since I became a Christian

Even when you’re out of sorts with food, your dishes are so creative!

The image of the cleaver is astonishingly apt. Cooking is no menial hobby; it’s hefty in importance! There’s no substitute for what it does in the home, for fellowship and for our bodies.

Kendall Vanderslice of Edible Theology is a great resource for thoughts at the intersection of food and theology!