High schoolers take so much for granted. I look back on my 15-year-old self with loving censure. Her perspective was so out of wonk, borderline delusional, and her world so engrossing that she never looked to see who was keeping it all together. This is a love letter to Mom, for Mother’s Day, and also to Dad because they come as a team, a symphony of fire and ice. It’s a love letter from Amelia right now, 25 years old and slightly wiser, but also a belated love letter from 15-year-old Amelia, that odd, ungrateful duck.

Dear Mom, thank you for…

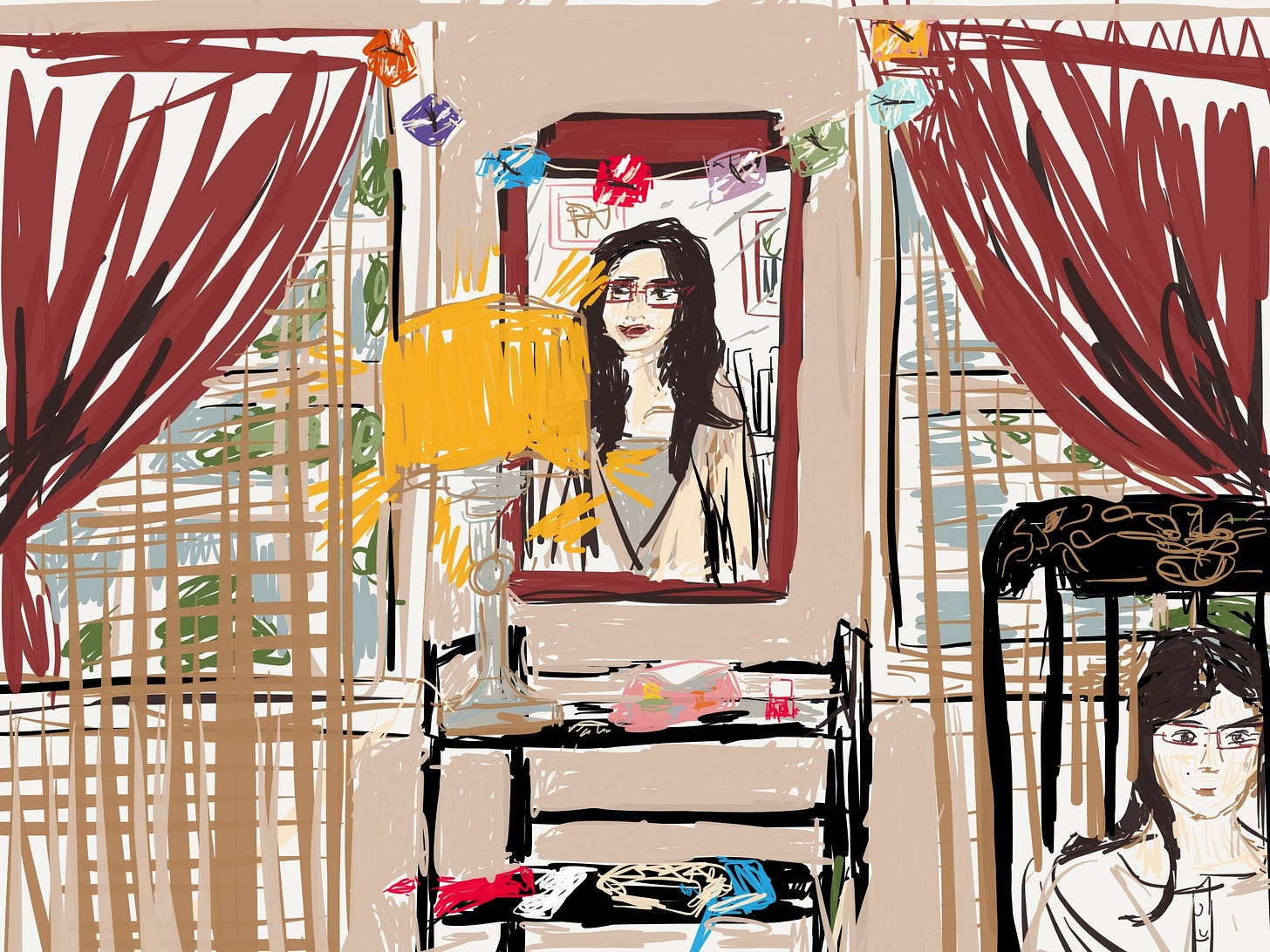

a warm place to return to after school.

In tenth grade, I had a friend with a mouth like a straight line and anxious eyes. His hair was always neatly side-parted, his long, bony fingers were always fiddling, he wore argyle sweaters and preppy socks, and he introduced himself with his first, second, and last name and the suffix “the III-rd” on the end. He spoke it in Roman numerals, in case you were wondering. Let’s call him Rupert for short.

After school, I would load up my enormous, black backpack with textbooks, loop my drawstring gym bag around one hand, and grab the disintegrating handle of my snakeskin violin case with the other. Rupert would stand by me with his leather briefcase (I kid thee not; no backpacks for him!), discoursing. (He did not talk. He discoursed.)

As I lugged myself home like a pack donkey, Rupert would tag along, his thin hands gesticulating in an excited, yet strangely formal manner. He would pause at the patisserie down the street from my house to grab a strawberry croissant. I would set down my violin and wait. Then, we would proceed onward—me sweating, him waving the croissant about.

We were usually debating the existence of God, or whether eating meat was ethical, or how much of the US budget should be devoted to military spending. You know, normal teenage stuff.

Rupert would follow me all the way home, up our long driveway and into the house that my family was renting from a literary fiction author named Alfie. The house was a Victorian relic painted a shocking shade of pepto-bismol pink with banging pipes and a secret spiral staircase running up its middle. Rupert would follow me straight in, shedding his shoes, never pausing in the discourse. My little siblings awaited his arrival with a secret glee because he would often leave his strawberry croissant half-eaten on the table, and they would scrounge it while he wasn’t looking. He never noticed.

Now that I’m older, I realize that he followed me home because he had nowhere else to go. He was a latchkey kid, the only child of divorced parents, with his mom married to a woman and his dad emotionally remote. He enjoyed the bustle of a busy house, my mom yelling at my brother to do his math, my dad’s warm and absent-minded, “Hello, children. What did you learn at school?”

He was drawn to that pink house like a moth to flame.

I am glad I never had to experience that kind of loneliness as a child. Mom, we could count on you to be there for us both when we needed you, and when we didn’t. It was good to know you would be there in both cases, that you loved us more than anything.

Thank you also for….

giving me permission to be weird.

I always found Rupert eccentric, but then, so was I.

I rejected teenage beauty standards by bundling my hair into a horrible topknot that a Greek girl told me looked like a dead squirrel. I dressed in a patchwork assortment of thrifted rags and formalwear. I wrote a novel over Thanksgiving Break about an angelic warrior who had her wings cut off by a demon, fell from space to Earth, and discovered a cabal of fallen angels called the Nephilim who were planning to storm both the angelic and demonic realms to establish their own planetary hegemony. I spent hours researching and practicing lucid dreaming, so that I could create stories even while unconscious. During Latin class, I built mind palaces, which I justified by filling with vocab words. I composed flowery, overwrought ballads and orchestrated them on our Yamaha. I befriended communists and fascists (the high school versions) and even a greasy-haired metalhead. I was completely oblivious to social hierarchy. Heck, who had time for that? I was too busy living!

If my parents had cared more about conventionality and fitting in, those years would not have been nearly so exciting. Thanks for not trying to force me into the cookie-cutter shape of a “popular” or “normal” girl.

And most of all, thank you for…

your annoying persistence when I tried to shut you out.

Mom, you are ferocious. You fight for your kids. Your love is fiery and raw and real. When I suffered from obscure emotional maladies, you would sense it and ask me if I was okay. Faced with the inevitable response of “I’m fine, mom,” you refused to walk away. Instead, you would sit on the side of my bed asking follow-up questions, attacking me with tickles, and being otherwise obnoxious.

That’s what I needed. I needed to know that my parents wouldn’t leave me when I was being difficult. I needed to know they loved me enough to fight me. I needed my mom to help me figure out what was going on inside because otherwise, I would never have even tried.

Dear Readers, what did your parents give you in high school that you didn’t appreciate until you reached adulthood?

Use the comments section to pay tribute to your moms.

Then, Ctrl-C your comment, open up your texting app, Ctrl-V into a chat with your mom, and press send.

All solid, all sweet. Very nice!

I got affectionate humility from my parents - we are a family of inveterate teasers, so that humor is a sign of intimacy that also makes sure no one can take themselves too seriously among relatives. My mom, naturally, led the way in that.

I love young Amelia. I also had a big black backpack that fit too many things 😂

I recently remembered the fact that there used to be carpet in my childhood home, hearing my parents whisper about how it was probably exacerbating my asthma, and then the carpet magically becoming hardwood. They always made big efforts seem simple, no brainers. Love is so mysterious.